Types and Characteristics of Amplifiers

While typically associated with audio equipment, amplifiers are fundamental components in a wide range of electronic circuits. In electronics, an amplifier is a device that boosts electrical signals by increasing input current or voltage. They amplify signals output from various sensors, preparing them for analog-to-digital conversion or driving loads.

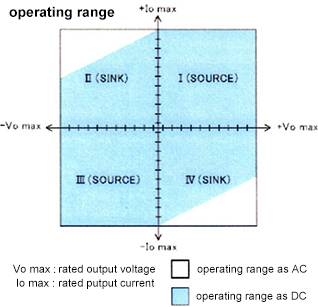

Amplifiers are the cornerstone of analog circuits; without them, modern analog electronics would essentially not exist. Furthermore, because amplifiers can control current and voltage (and thus power), they function as the core technology in high-precision power supplies. In this context, a standard DC power supply can be considered a unipolar amplifier, capable of supplying power in only one polarity.

In contrast, a Four-quadrant Bipolar Power Supply can source and sink current in both positive and negative voltage polarities. We will discuss this technology in detail in the final section.

There are two main categories of amplifiers: Linear Amplifiers and Digital Amplifiers (Switching Amplifiers).

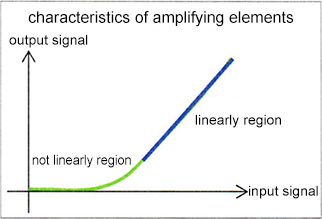

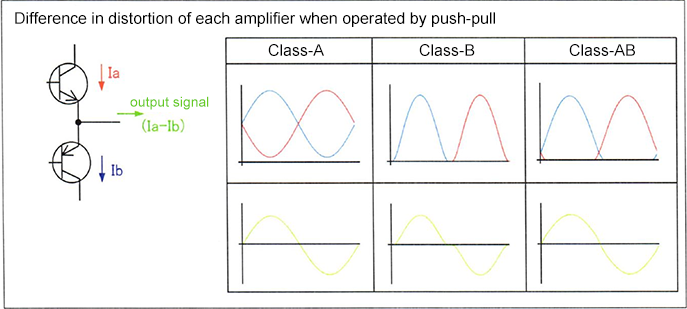

A linear amplifier utilizes the linear region of amplifying elements, such as transistors and FETs. However, due to the physical characteristics of these elements, output signals can become non-linear near the zero-crossing point, causing distortion. Amplifiers are classified based on their operating point (bias) to address this issue:

Class-A Amplifiers

Class-A amplifiers use the amplifying element solely in its linear region. While this offers excellent linearity, it requires a continuous bias current even when the input signal is zero. This results in high fidelity but lower efficiency and increased heat generation.

Class-B Amplifiers

Class-B amplifiers operate with zero bias current, conducting only when a signal is present. While this significantly improves efficiency compared to Class-A, it introduces "crossover distortion" when the signal waveform crosses zero.

Class-AB Amplifiers

Class-AB amplifiers are a compromise between Class-A and Class-B. By applying a small bias current to a Class-B design, crossover distortion is effectively eliminated while maintaining better efficiency than Class-A designs.

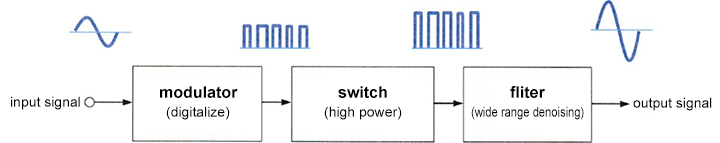

Another amplifier is a "digital amplifier," also called a switching amplifier, class-D amplifier. This is more efficient and smaller than linear amplifiers by using switching techniques such as PWM. It is mainly used for compact audio power amplifiers such as automotive applications. Although MOSFETs and IGBTs are used as switching devices, there is also the problem that the frequency band of the corresponding input signal is narrow.

Key Considerations for Stable Amplifier Operation

To ensure stable voltage and current output, it is essential to understand the factors that limit amplifier performance.

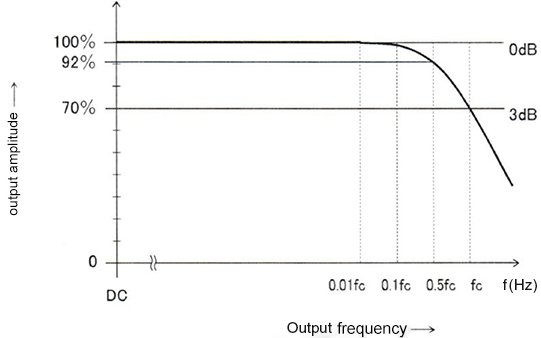

Frequency Bandwidth

The frequency bandwidth defines the operating speed of the amplifier. As frequency increases, the amplifier's ability to track the input signal diminishes, causing the output amplitude to decrease. The bandwidth is typically defined as the frequency at which the output amplitude drops to -3 dB (approximately 70% of the input).

For example, if a 120 V rated amplifier has a 20 kHz bandwidth, attempting to output a ±20 V sine wave at 20 kHz will result in an output of roughly ±14 V (-3 dB). Therefore, users must select an amplifier with sufficient bandwidth margin for the target frequency. Bandwidth is directly related to response speed. The rise time (tr) of an amplifier with a frequency bandwidth (fc) can be approximated by: tr ≑ approx 0.35 / fc

Slew rate

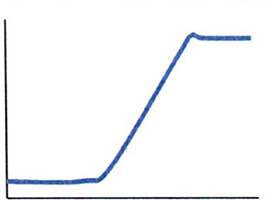

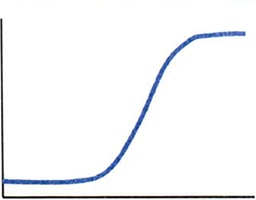

The second factor is a slew rate that represents the response speed of the amplifier. This shows the maximum voltage rise rate of the amplifier. Generally, it is expressed by the amount of voltage change per microsecond. The response speed of the amplifier may be limited by the frequency band or by this slew rate. When the step response is limited by the slew rate, the rising waveform becomes straight, as shown in the figure.

the case limited by slew rate

the case limited by frequency band

Inductive Loads (e.g., coils, electromagnets, motors)

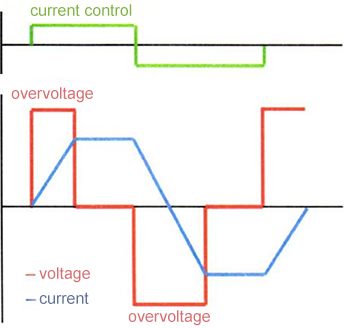

For inductive loads, the voltage-current relationship is defined as . When operating at high speeds under Constant Current (CC) control, rapid changes in current induce a significant counter-electromotive force (voltage spike). If this voltage exceeds the amplifier's rating, the overvoltage protection circuit may trigger, clamping the waveform and preventing accurate reproduction of the input signal. To avoid this, select a model with a voltage rating that accommodates the induced spikes, or reduce the rise speed of the input signal.

This is a critical consideration in applications such as the high-speed driving of magnetic coils or testing automotive solenoids.

For example, when trying to output a square wave with a fast rise speed, the desired waveform may not be obtained because the voltage is limited by the overvoltage protection. In such a case, it is necessary to slow the rising speed of the input signal and select a model that supports the generated voltage.

In addition, using a step-like signal such as digital control for the input signal will generate many voltage pulses as well. As these pulses may create a problem, it is recommended to use continuous waveform input signals as much as possible.

On the other hand, overvoltage protection also limits the output signal. However, if the output signal is suddenly turned off, the protection does not work and a large voltage may be generated from the inductive load.

Capacitive Loads (e.g., capacitors, piezoelectric actuators)

For capacitive loads, the relationship is governed by . Unlike inductive loads, driving capacitive loads at high speeds under Constant Voltage (CV) control requires large peak currents. If the amplifier cannot supply sufficient current, the voltage waveform will become distorted (slew-rate limited). When driving high-capacitance devices like piezoelectric actuators, ensure the power supply's peak current rating meets the application requirements.

When driving piezoelectric elements for precise positioning, a large peak current is required for rapid voltage changes.

Diode Loads

When driving a load via a diode (or a load that only allows unidirectional current), standard power supplies may face issues. Under Constant Current (CC) control, even if the setpoint is zero, slight internal offset currents can cause the output capacitor to charge. Since the diode blocks reverse current, the power supply cannot sink current to discharge the capacitor, causing the voltage to drift upward until it hits the overvoltage protection limit. To prevent this, a bleeder resistor or a bi-directional (bipolar) power supply may be required to ensure proper voltage control.

Capacitance and inductance of cable

Last factor is the cable. When operating the amplifier at high speed, we cannot ignore the effects of the capacitance and inductance of the cable for the output signal. In high-voltage amplifiers, the cable has a capacitance between the output wire and the shield, so the capacitance affects the rising speed of the voltage waveform. The longer cable has a greater capacity. This is the reason for using a low electrical resistance cable among music enthusiasts and building a system that minimizes the length of the cable.

In addition, in the low-voltage, high-current model, the inductance of the cable and the inductance generated by the wiring method greatly affect the rise speed of the current waveform. This can be mitigated to some extent by making the current loop smaller, such as twisting the wiring.

Four-quadrant Bipolar Power Supplies

Finally, we introduce the Four-quadrant Bipolar Power Supply. Unlike general DC power supplies that only output positive voltage and current (single quadrant), a bipolar power supply can source and sink current across both positive and negative voltages (four quadrants).

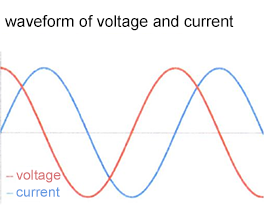

This capability makes bipolar power supplies essentially high-power, high-speed operational amplifiers. They are ideal for driving inductive loads (L) and capacitive loads (C), where the phase difference between voltage and current means the power supply must alternately source and sink energy.

Under constant-voltage (CV) control, a four-quadrant bipolar power supply output voltage corresponds to the input signal. At this time, the output current can take value freely if it is within the rating. Similarly, under constant-current (CC) control, it outputs current according to the input signal. At this time, if the output voltage is within the rating, it can be a positive or negative free value.

However, because the output protection is performed by the overvoltage protection and the overcurrent protection, the desired waveform may not be obtained. It is desirable to operate so that both voltage and current are within the rating, and it is important for stable use of the power supply to understand the characteristics of the load.

Key Advantages:

- True Bipolar Output: Smoothly crosses zero volts from positive to negative without switching glitches.

- Source and Sink Capability: Can absorb energy from the load (sink) as well as supply it (source), essential for active braking of motors or discharging capacitors.

- High-Speed Response: Suitable for waveform generation and simulation applications.

While powerful, users must still ensure that the operation remains within the voltage and current ratings of the device.

Related Technical Articles

Recommended products

Matsusada Precision's high-performance Amplifier and Bipolar power supplies

Reference (Japanese site)

- Japanese source page 「アンプの利用と、その注意点」

(https://www.matsusada.co.jp/column/column-amp.html) - D級アンプ:基本動作と開発動向

https://www.maximintegrated.com/jp/app-notes/index.mvp/id/3977 - 周波数特性とは(電子回路設計 入門サイト)

(https://www.kairo-nyumon.com/analog_frequency.html)